Happy New Year 2026! I honestly cannot believe it is already another year. Looking back, 2025 feels like it passed in a blur of late nights, deadlines, competitions, and moments that quietly changed how I think about learning. This blog became my way of slowing things down. Each post captured something I was wrestling with at the time, whether it was research, language, or figuring out what comes next after high school. As I look back on what I wrote in 2025 and look ahead to 2026, this post is both a reflection and a reset.

That sense of reflection shaped how I wrote this year. Many of my early posts grew out of moments where I wished someone had explained a process more clearly when I was starting out.

Personal Growth and Practical Guides

Some of my 2025 writing focused on making opportunities feel more accessible. I wrote about publishing STEM research as a high school student and tried to break down the parts that felt intimidating at first, like where to submit and what “reputable” actually means in practice.

I also shared recommendations for summer programs and activities in computational linguistics, pulling from what I applied to, what I learned, and what I wish I had known earlier. Writing these posts helped me realize how much “figuring it out” is part of the process.

As I got more comfortable sharing advice, my posts started to shift outward. Instead of only focusing on how to get into research, I began asking bigger questions about how language technology shows up in real life.

Research and Real-World Application

In the first few months of the year, I stepped back from posting as school, VEX Robotics World Championship, and research demanded more of my attention. When I came back, one of the posts that felt most meaningful to write was Back From Hibernation. In it, I reflected on how sustained effort turned into a tangible outcome: a co-authored paper accepted to a NAACL 2025 workshop.

Working with my co-author and mentor, Sidney Wong, taught me a lot about the research process, especially how to respond thoughtfully to committee feedback and refine a paper through a careful round of revision. More than anything, that experience showed me what academic research looks like beyond the initial idea. It is iterative, collaborative, and grounded in clarity.

Later posts explored the intersection of language technology and society. I wrote about AI resume scanners and the ethical tensions they raise, especially when automation meets human judgment. I also reflected on applications of NLP in recommender systems after following work presented at RecSys 2025, which expanded my view of where computational linguistics appears beyond the examples people usually cite.

Another recurring thread was how students, especially high school students, can connect with professors for research. Writing about that made me more intentional about how I approach academic communities, not just as someone trying to get a yes, but as someone who genuinely wants to learn.

Those topics were not abstract for me. In 2025, I also got to apply these ideas through Student Echo, my nonprofit focused on listening to student voices at scale.

Student Echo and Hearing What Students Mean

Two of the most meaningful posts I wrote this year were about Student Echo projects where we used large language models to help educators understand open-ended survey responses.

In Using LLMs to Hear What Students Are Really Saying, I shared how I led a Student Echo collaboration with the Lake Washington School District, supported by district leadership and my principal, to extract insights from comments that are often overlooked because they are difficult to analyze at scale. The goal was simple but ambitious: use language models to surface what students care about, where they are struggling, and what they wish could be different.

In AI-Driven Insights from the Class of 2025 Senior Exit Survey, I wrote about collaborating with Redmond High School to analyze responses from the senior exit survey. What stood out to me was how practical the insights became once open-ended text was treated seriously, from clearer graduation task organization to more targeted counselor support.

Writing these posts helped me connect abstract AI ideas to something grounded and real. When used responsibly, these tools can help educators listen to students more clearly.

Not all of my learning in 2025 happened through writing or research, though. Some of the most intense lessons happened in the loudest places possible.

Robotics and Real-World Teamwork

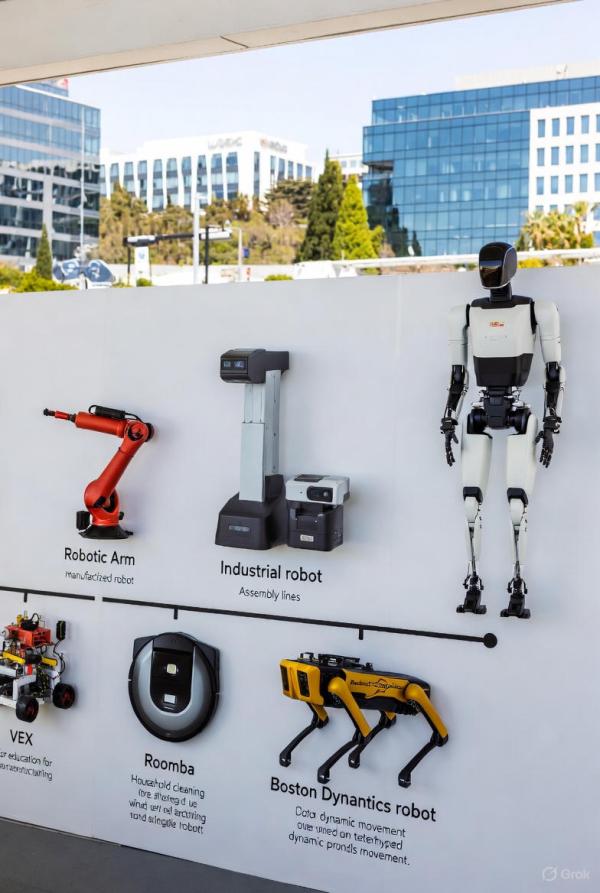

A major part of my year was VEX Robotics. In my VEX Worlds 2025 recap, I wrote about what it felt like to compete globally with my team, Ex Machina, after winning our state championship. The experience forced me to take teamwork seriously in a way that is hard to replicate anywhere else. Design matters, but communication and adaptability matter just as much.

In another post, I reflected on gearing up for VEX Worlds 2026 in St. Louis. That one felt more reflective, not just because of the competition ahead, but because it made me think about what it means to stay committed to a team while everything else in life is changing quickly.

Experiences like VEX pushed me to think beyond my own projects. That curiosity carried into academic spaces as well.

Conferences and Big Ideas

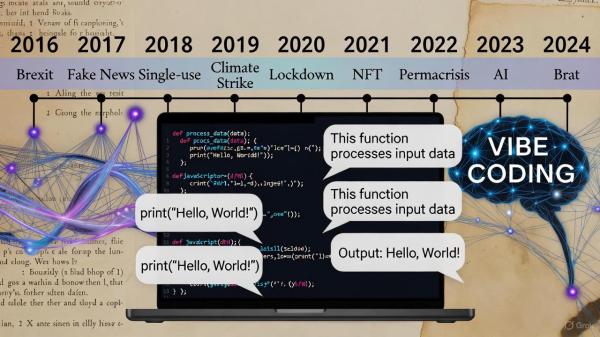

Attending SCiL 2025 was my first real academic conference, and writing about it helped me process how different it felt from school assignments. I also reflected on changes to arXiv policy and what they might mean for openness in research. These posts marked a shift from learning content to thinking about how research itself is structured and shared.

Looking across these posts now, from robotics competitions to survey analytics to research reflections, patterns start to emerge.

Themes That Defined My Year

Across everything I wrote in 2025, a few ideas kept resurfacing:

- A consistent interest in how language and AI intersect in the real world

- A desire to make complex paths feel more navigable for other students

- A growing appreciation for the human side of technical work, including context, trust, and listening

2025 taught me as much outside the classroom as inside it. This blog became a record of that learning.

Looking Toward 2026

As 2026 begins, I see this blog less as a record of accomplishments and more as a space for continued exploration. I am heading into the next phase of my education with more questions than answers, and I am okay with that. I want to keep writing about what I am learning, where I struggle, and how ideas from language, AI, and engineering connect in unexpected ways. If 2025 was about discovering what I care about, then 2026 is about going deeper, staying curious, and building with intention.

Thanks for reading along so far. I am excited to see where this next year leads.

— Andrew

4,600 hits